The death penalty was reinstituted in Pennsylvania in 1976. Despite having the fourth largest death row inmate population in the country for over two decades, only three inmates have been executed in Pennsylvania since the reinstitution. We will take a look at the tumultuous history of the death penalty in Pennsylvania, the future of the punishment, and what life is like on death row.

History of the Death Penalty

The death penalty is a highly contested practice, and an extremely polarizing source of public debate. While some argue that the punishment is cruel and archaic, others maintain that the death penalty is an appropriate form of justice and deterrence for the most heinous of crimes. Public opinion and policy in Pennsylvania has wavered between the two opposing views for generations.

In 1834, Pennsylvania became the first state to outlaw public executions. The gallows were moved to the prisons and inmates were executed without a large public spectacle. In 1972, the death penalty was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Furman v. Georgia, and was reinstated by subsequent 1976 Supreme Court rulings known collectively as the Gregg decision. Prior to the Gregg decision, Pennsylvania carried out the third most executions of any state in the country.

After the reinstitution, many men and women continued to be sentenced to death for their crimes. For more than two decades following the Gregg decision, Pennsylvania had the fourth largest death row inmate population in the country. However, during those two decades and the decades to follow, the state essentially stopped executing. Only three inmates, or .7% of Pennsylvania’s death row population, have been put to death since 1976.

The Executed

The three men who have been executed in Pennsylvania have all been “volunteers”; meaning, that they waived their rights to an appeal process for their sentence. Additionally, all three were found to have serious mental health issues.

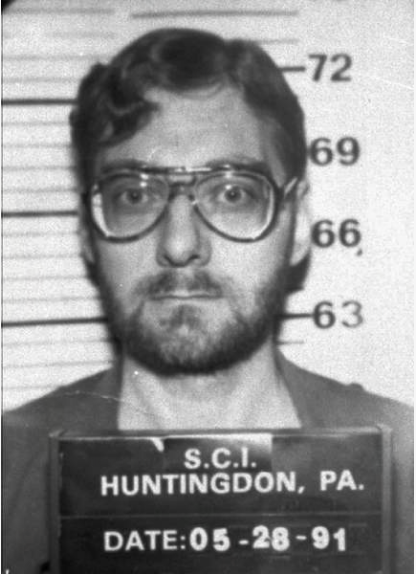

Keith Zettlemoyer

Keith Zettlemoyer was the first person executed in Pennsylvania since 1962. Zettlemoyer was also the first person to be executed by means of lethal injection in state history. He was convicted of the 1980 murder of Charles DeVetsco, a friend who planned to testify against him in a robbery trial. Zettlemoyer begged the courts to let him die because his “brain disease” made his life in prison hell (NYT). He was put to death in May 1995 at the State Correctional Institute- Rockview in Bellefonte, PA.

Leon Moser

Leon Moser was the second person executed in Pennsylvania after the reinstitution of the death penalty. He was put to death by lethal injection in Bellefonte in August of 1995. Moser, a one-time seminary student and a former Army lieutenant, was convicted of killing his ex-wife and two daughters outside of a church on Palm Sunday in 1985. While in prison, he underwent psychiatric treatment. During his plea hearing, Moser told the judge, “I request the death penalty and that it be carried out as soon as possible”.

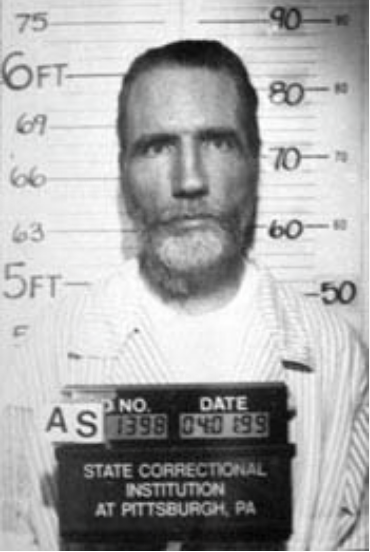

Gary Heidnik

Gary Heidnik is the last person executed in Pennsylvania. Although he maintained his innocence until his death, he did not fight his sentence. It was Heidnik’s hope that his death would end executions in the state.

Heidnik was known sensationally as the “House of Horrors” killer. He was convicted of torturing and killing women in the basement of his Philadelphia home. Heidnik was a disabled Army veteran who suffered from schizophrenic delusions. He was put to death in 1999 by lethal injection in Bellefonte.

The Exonerated

The death row inmate population has decreased from 246 in October 2001 to 156 in January of 2018 without any executions. This decline is mostly due to resentencing to life or less, acquittals, exoneration, and death sentences being overturned. Six death row inmates have been found innocent and released from death row.

Nicholas Yarris is one of the exonerated. In 1982, a young woman was abducted, raped, and murdered on her way home from her job at the mall. Several eyewitnesses placed Nicholas Yarris at the scene. Based on circumstantial evidence, he was convicted of the crime and sentenced to death. With the advent of more sophisticated DNA testing in the early 2000’s, evidence was retested. Blood on the killer’s gloves, skin from under the victim’s nails, and semen from the victim’s underwear were all concluded to come from the same source- Nicholas Yarris was not a match. Yarris was exonerated in 2003 after spending 21 years in prison.

Harold Wilson is the most recent and one of the most highly publicized acquittals. Wilson was sentenced to death for the 1988 home invasion and ax murders of Dorothy Sewell, her nephew, and his girlfriend. The conviction largely rested on a blood splattered jacket recovered from Wilson’s basement by police. During the appeals process, serious racial bias against the defendant came to light- the prosecution purposefully stuck all black jurors during jury selection. Post-conviction DNA testing revealed additional shocking information- there were four sources of blood found on the jacket. Experts concluded that the four profiles on the jacket belonged to the victims and the killer. Three profiles did, in fact, match the victims’; however, Wilson did not match that fourth profile. He was acquitted of the murder charges in 2005.

Among the others acquitted or exonerated were Jay Smith, a former high school principal sentenced to death for the brutal murders of a woman and her two children; Thomas Kimbell, a neighborhood menace who was convicted of the 1994 murders of a mother and two children based on the tainted testimony of a jailhouse informant; Neil Ferber, whose murder charges were dismissed due to the failure of the prosecution to disclose exculpatory evidence, and misinformation provided by the manipulated testimonies of a jailhouse informant and an eyewitness; and William Nieves, who was acquitted during retrial when his new counsel was able to argue the inconsistencies in the key witness’s identification of the killer.

Life on Death Row

On February 13, 2015, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf announced a moratorium on executions. In a press release, the governor said,

“This moratorium is in no way an expression of sympathy for the guilty on death row, all of whom have been convicted of committing heinous crimes. The decision is based on a flawed system that has proven to be an endless cycle of court proceedings as well as ineffective, unjust, and expensive. Since the reinstatement of the death penalty, 150 people have been exonerated from death row nationwide, including six men in Pennsylvania.”

In addition to wrongful convictions, Governor Wolf cited racial bias and the negative effect of executions on the victims’ families as support for his decision to impose the moratorium.

Although Governor Wolf maintains his position on capital punishment, GOP gubernatorial candidate, Scott Wagner, is committed to reinstituting the practice. If elected, Wagner promises to overturn the moratorium within his first 48 hours as governor.

The moratorium does not prevent individuals from being sentenced to death. There are still more inmates joining the ranks on death row. Those death row inmates are hanging in the balance of speculative pieces of legislation, sentenced to death in a state that has only chosen to execute .7% of the people who have been handed the same fate. Though lethal injection will likely never come to those 156 men and women, life on death row can be perceived as punishment enough.

In Pennsylvania, death row inmates are automatically and permanently placed in solitary confinement. Other prisoners in Pennsylvania may be placed in solitary confinement; however, their condition is often temporary. By exhibiting good behavior, other prisoners may be placed back in general population. For death row inmates, no administrative review or positive exhibition can free them of their isolation.

For Mother Jones, Nathalie Baptiste reports, “On most weekdays, [death row inmates] spend 22 hours in cells that are roughly the sizes of parking spots. On weekday mornings, they are allowed two hours of outdoor exercise in a small enclosure.” During the weekends, there is no break from the confinement; from Friday morning to Monday morning, inmates on death row endure 70 hours without human interaction.

Of the 156 men and women on death row in Pennsylvania, 80% have spent over a decade in solitary confinement. Studies have found that individuals kept in isolation exhibit similar symptoms including memory loss, panic attacks, and suicidal thoughts/actions. Additions symptoms like hypersensitivity to sights/sounds, paranoid thoughts, and hallucinations can be observed within the first few days of isolation.

The Marshall Project‘s July 2017 Survey of State Corrections Officials concluded that, “Of the 31 states with a death penalty, 20 allow condemned inmates less than four hours of out-of-cell recreation time each day. One state, South Dakota, permits just 45 minutes of daily out-of-cell recreation time.” Inmates in many states, including Pennsylvania, have filed lawsuits claiming that death row conditions violate their constitutional rights. Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, North Carolina, Tennessee, Missouri, Virginia, and even Louisiana’s Angola Prison (made infamous by the Netflix documentary, 13) have changed their death row policies due to legal and political pressures.

Pennsylvania’s policy of housing death row inmates in solitary confinement is a meek effort to protect the general population of a prison by segregating those criminals deemed to be the most heinous and dangerous. Case studies, however, reveal that prisons experience less violent attacks and less recidivism as a whole when solitary confinement is not implemented.

Putting death row conditions on the public agenda is an arduous task. It is understandably hard for most of society to care about the treatment of individuals convicted of “evil” crimes. Statistically, death row inmates are far more likely to have their sentenced reduced or the charges against them dropped than be executed. We may be conditioned to think that death row is merely a waiting room between the courtroom and the chair, but it may be more appropriate to think of death row as a waiting room between the courtroom and reentry into society.

An 1890 Supreme Court decision on solitary confinement reads, “a considerable number of the prisoners fell, after even short confinement, into a semi-fatuous condition, from which it was next to impossible to arouse them, and others became violently insane; others committed suicide, while those who stood the ordeal better were not generally reformed, and in most cases did not recover sufficient mental activity to be of any subsequent service to the community.”

One in twenty five people sentenced to death are innocent. For every ten people executed since 1976, one person has been exonerated and freed from death row.

Should we condemn Americans to death and- if not death- automatic and permanent solitary confinement when our margin of error is so great? If we acknowledge that mistakes are common and inevitable, we have a responsibility to ensure that inmates are not held in conditions which render them incapable of “subsequent service to the community”.

• • • • • • •

Your representation needs do not stop at the verdict. We may be able to help with PCRA claims, expungements, and appeals. If you or a loved one has been arrested for or convicted of a crime, please call the attorneys at Rehmeyer & Allatt for a free consultation.